The Role of HR in a Continuous Improvement Organization: Attitude Towards Problem Solving

(Reposted by permission of the author from LinkedIn)

When Toyota began its search for a better way of doing business, they had no Toyota Production System. They knew their issues and were searching across the globe for answers. They could have just imitated the best car makers in the world, Ford and GM and created something that was “their” version. The question for all of us is why didn’t they?

What they knew about their people was that they were never going to accept pure imitation and were going to find ways to go back to the old ways if the place they were aiming for was not their own. This is highly descriptive of almost all the companies I have worked with over more than 20 years of consulting in continuous improvement cultures called lean.

Toyota chose the logical way forward and began earnestly to create a culture and system of production. They chose to achieve their aims with a clear vision of where they were going and activity based on problem-solving. As they proceeded, it was obvious that the elements of the problems solved had a synergy with the ultimate aim of success; they defined waste and chose to attack it through problem-solving. Toyota was very clear that progress was based on good thinking and the system will get better through kaizen or small change. They knew, as most of us do, that immediate system-wide change will not create the reliability of products they pursued.

Thanks to their work, the image of lean implementation is very clear and attractive. However, there is a drawback that is a constant in every company I have worked with: problems are many and the availability of resources is scarce. This forces companies to either give up and continue to tweak the workplace ad-hoc or to take one small area and try the complete system as they know it.

Two questions consistently arise at this point:

1. How can we put in a new system under the pressure of production?

2. If we are not a part of the implementation, why are our problems being ignored?

If you examine the Toyota Product System (TPS) carefully, you will find that the architecture of implementation is known, rational & sequenced. First, the customer needs to be protected and quality is the theme that is the most important through a series of stability. Quality and productivity are next followed by quality, productivity and cost. The actual architecture is Stability, Continuous Flow, synchronized production, pull and level production. What each of these serves to do is provide focus to decide what problems need to be solved.

Problems can be contentious because the definition of a problem is a deviation from a standard. When performance is variable then a problem becomes a deviation from a standard or expectation. Of course, the first step in solving a problem is to determine what the standard should be and then focus your efforts on getting the standard performed reliably. This issue is of the utmost importance to HR. Problems are tests of leadership. If the response is slow or even non-forthcoming, then the message is clear. “Don’t rock the boat”. For the person who lives with a problem for a long time, the message is clear, “You do not respect my role, my issues nor my generation of waste.” In HR terms, there is no mutual trust and respect. This will keep on generating poor relations and will not use the potential every employee has for solving problems. Furthermore, it will put leadership in a deficit for capacity, cost, quality and relations with all who are aware of the response. HR will not be able to serve their role effectively as they fight the poor attitudes generated by disgruntled employees.

All of this is straight forward; it sets the challenge for problem-solving. The answer lies in the underlying disciplines. First, you have to acknowledge that you have a problem. In an organization where management’s role is to execute the plan, any deviation is seen as an inconvenience. Of course, management rarely experiences the actual problem and considers any disruption to the plan an opportunity to blame. Since management’s usual style is to blame supervision, and supervisors are generally focused on keeping management off their back, they pass the blame along. For the person who experiences the problem, they learn to never lift up problems again. What is lost is the discipline of trust, causing a sense of dissonance from management.

The next underlying discipline is the role. The role gets connected with governance expectations only when everyone looks upon everyone else like a link in the performance chain. Governance provides the structure through which problems are solved. All problems follow a set process involving, at a minimum, five levels of review for alignment to the system of work. The team leader coaches the member in how to collect data and follow the standard process. The supervisor and the HR representative review the solutions for alignment to cultural expectations. The Manager reviews the content to ensure facts are being used and opinions are not and the support organization reviews the solutions to ensure they can be supported.

If I am a value adder and I experience a deviation from my standard, I have an obligation under my role to signal to my team leader. It is known that the value adder will ignore deviations unless they get immediate attention to their problem. For the standard process to work, the next level above the value adder, the team leader, must respond to the signal and either recognize the solving the problem by the value adder or put in place a temporary countermeasure until the problem is solved. By doing this, the team leader is clearly empowered to support the lifting up of problems and putting a temporary action into place. During this entire process, the value adder keeps ownership of the problem and accountability. Problems that are not solved with the temporary countermeasure must be lifted up to the Supervisor who seeks whatever support is necessary for the value adder.

The next discipline is a sense of urgency. For the manager, this discipline requires them to understand the problems and put a sense of urgency into solving at the root cause. The value adder experiences this as the company valuing their problems with a willingness to put resources into making sure the process flows smoothly and predictably. This urgency builds trust from the value adder, the team leader and the supervisor. This trust supports them having an enhanced sense of urgency in solving problems.

The significance of problems is that they come in two forms. The most common one is a deviation from the standard. The second one is non-value-added work, called waste, contained within the standard. Waste is the basis of kaizen or continuous improvement activities. The value-adder, as a standard, is given time to analyze their standardized work and find waste. Once they have done this, they find ways to eliminate waste. The organization is standing behind them to give them time, expertise and other resources to assist. The key is that the process of improvement is a learning and confidence building experience. The organization must be careful not to take problem-solving away from them. It must be clear that any resource provided to them will be supporting only.

Urgency is not always straight forward. The pressure to produce can mask any situation. For the leader, this is a particularity difficult problem as they have so many opportunities to improve and so little time to solve them. It is critical that the leader makes the best use of their time. So, the question is, how should a leader best spend their time in the process of problem-solving? The answer is very straight forward but difficult to maintain as a discipline. Problem-solving presents many opportunities for solving problems and promoting the way forward. The leader encourages critical thinking and creates the place and time for leadership to show up and make a difference. As a leader, each of these actions and places are linkages to demonstrate the importance of fighting the status quo but also encourage the sense of urgency around solving problems. It follows that the leader must spend the majority of their time determining the way forward with emphasis on solving problems. It is also clear that the role of coaching execution not only supports problem-solving but also allows the leader to pass on their expertise. This creates a sense of urgency in problem-solving and executing the plan.

The discipline of prioritization must be followed. When value adders are asked to find problems, they find hundreds. The question of where to start is key. The answer is in getting problem-solving into the whole workforce. This is done by setting the expectation that problems that can be solved by the value adders come first. The emphasis is placed upon insisting that any problem must be solved by the person who has identified it. This limits the value adder to looking at only their job. Problems outside of the individual’s job should be considered a priority only in the context of safety first and annual goals, in that order. Making everyone aware of the priorities and have a sense of urgency causes the organization to trust that the problems will be solved.

The last discipline is recognition of problem-solving as a key part of the lifeblood of the organization. Encouragement and support are vehicles. Recognition can come from the suggestion system, from recognition meals and from the management doing their gemba and thanking the value-adder for good thinking. The most valued suggestion or problem solved is not the one that attracts recognition. Recognition must be seen as deserved from alignment to purpose. The most important recognition is by a manager recognizing that the problem-solving activity is robust. Mutual trust and respect create an atmosphere where improvement lies.

If these disciplines are enhanced, the level of problem-solving will persist at a high level. Once the flow of problems increases it is up to the leadership to expand its use by promoting experimentation. Countermeasures should be tried before achieving the outcomes desired. All problem solving has an aspect of trying the idea. What is consistently encouraging is if the problem solution does not solve the problem the leader will consistently decide to continue to search for a root cause. Those who do the problem solving and enact a solution find that blame is not present and problem-solving is a constant practice.

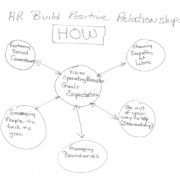

HR plays a vital role in problem-solving culture. First, it sets the expectation for finding and solving problems. Then they teach the value adder how to think logically and how to execute the standard process for problem-solving. HR also monitors and supports the problem-solving activity in the workplace by coaching the supervisors, the team leaders and the team members in how to achieve critical thinking using the standard process.

Because of the collaborative nature of problem-solving, HR constantly monitors the relationship between the problem solver and their supervision, so the aim of mutual trust and respect is honored. It is important to keep in mind that problem-solving is just one aspect of the production system. Any interaction must stand the test of review and support from the rest of the organization. The rule is that anyone affected by the problem solution must have their support confirmed. Those involved must review critical thinking and ensure that it does not disrupt the culture of the workplace.

2019, Total Systems Development, Inc.

2019, Total Systems Development, Inc. 2019 Total Systems Development

2019 Total Systems Development

2019, Total Systems Development

2019, Total Systems Development

2019 Total Systems Development

2019 Total Systems Development