The Path to a Problem Solving Culture, Part 2

Part 2 of a Series

Leadership – the Essential Element

In my last post, I evaluated the options for , as the starting point for developing a problem solving culture. But it is a simple fact that while training may transfer knowledge, it is not enough to transform behavior. The missing element, the one that embeds actions into the daily routine until they become a part of culture, is leadership. And by leadership, I don’t mean distant directives or half measures designed to “show” the workforce that leaders endorse the latest improvement effort. I mean a coherent and responsive driving force that supports communication, transparency and discipline in a blame-free environment. Demonstrating such leadership is hard work and revealed in the constant pursuit of five integrated attributes described below.

1. Clearly defined vision, strategy & goals that are communicated thoroughly

1. Clearly defined vision, strategy & goals that are communicated thoroughly

Vision – As the leader, your task is to formulate a vision about how you’d like the organization to behave when a problem occurs. For example, there is an immediate trigger signaling a problem, a supervisor goes to the site to observe, from all perspectives, with the person closest to the problem. An investigation ensues, others are brought in, discussions continue, and the supervisor facilitates the problem solving process. Countermeasures are installed, the change is monitored in a follow-up procedure and if successful, standard work is revised. Specific behaviors are imagined in order to formulate a vision of “solving problems with a sense of urgency.”

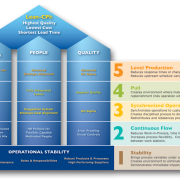

Strategy – When your people are first deployed to solve problems, they’ll likely be overwhelmed with the magnitude of the task. Problems are deviations from standards, and there will be an ever-expanding list of problems. Even if your existing standards are for quality, delivery and safety. Even if standard work and visual management is absent. One strategy to lessen the anxiety is to set boundaries on the focus of your problem solving activities for a fixed period (6 months, 1 year, etc.) A strategy I’ve found invaluable is what I call “small focus, big results.” After analyzing the data from an aggregate of problems, and if the organization finds that quality problems have the highest impact, and specifically those attached to a specific product, then it follows that you should work those issues. A Pareto diagram is helpful, as is the Pareto principle that, for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.

Goals – Once focus is fixed, the problem solving team as a group must define its goals, that is, how much to improve. In a mature problem solving culture, the team holds a “catch-ball” session (someone articulates the project’s purpose objectives and goals, then “throws” those ideas to other stakeholders for feedback, support and action). In this way, the team uses data to decide how fast and how far they can move the quality needle. An organization just starting effort to transform culture picks a memorable and achievable percent using their best judgment, in relation to the problems and their estimated impact. It doesn’t have to be too easy, but it certainly doesn’t have to be too difficult. The real challenges can come later when the organization operates as a highly efficient and effective problem solving machine.

Communication – Once you have the vision, strategy and goals formulated, you must communicate them. Simply saying “Our organization solves problems with a sense of urgency” is not enough. You must paint the picture of what that means in terms of individual behavior. Also, it should be compelling and aligned to the business strategy, such as, “Solving dozens of small problems daily over the last year has resulted in quality costs reaching an all-time low.”

This can be done during “town halls,” cascading down from leaders who deliver it to their direct reports, who in turn deliver it to their direct reports and so on. It should be written, everywhere and communicated often; don’t just have one big show where you tell everyone about it then move on. I have one tip though; don’t go down this road unless you are willing to commit. I’ve seen too many organizations where the employees have very little trust that leadership will follow through with things. When I enter an organization and hear the word “flavor of the month” come from a shop floor employee, I immediately go to work with leadership on reflecting why this is and what can be done differently this time around to regain the trust of the people.

2. Governance

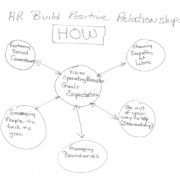

One way to demonstrate commitment is to remain involved every step of the way, and one way to remain involved is for leadership to establish a 3-tiered system of governance. This not only provides direction but also demonstrates on-going support.

Steering Committee – This is a group of leaders that sets goals and direction, approves plans, spending and resources, and checks results. It meets to discuss results, the failure to meet targets, and the response. This group’s function is to drive accountability, demonstrate support and help overcome barriers when they present themselves. The group can reach across the organization, provide funding, and influence policy.

Implementation Group – This is every transformation’s central nervous system. It analyzes results, develops plans and coordinates resources. Each member of this team has spent significant time learning and improving their problem solving competencies to the extent that they are able to train and support others. Also, they are skilled facilitators that lead small groups through sessions. Their main goal is to drive behavior changes through frequent interactions with employee stakeholders. They spend a lot of time on the ground floor, observing people, looking for the right behaviors and reinforcing good problem solving when it should be occurring. This includes coaching sessions. In the early phases of the implementation, this group is the keeper of the culture. The members work to gain critical mass in the organization; get enough people to behave according to standards in order to gain velocity in the change. To do this, they not only reinforce problem containment and a sense of urgency, but also facilitate temporary groups that solve more complex problems.

Work groups – These are temporary in nature and typically formed around a single problem, generally a vexing one that requires more time, resources and effort to solve. These groups are comprised of technical and process experts in different functional areas that support the broken process. For example, production personnel – people who actually do the process, a product engineer – someone who knows the product well, a quality engineer – someone who understands key quality characteristics, a purchaser – someone who interfaces with vendors, and a member of the implementation team to uphold problem solving standards and record progress to plan and results. Good judgment is essential in choosing work group members.

Governance is, at its core, a support system, vital for achieving the goals that support the problem solving culture. Work groups find support from the implementation team, which provides coordination, facilitation, knowledge and serves as a resource for lifting barriers. The implementation team finds support from the steering committee, which provides a strategic business perspective, removes big barriers and provides direction and accountability. The steering committee’s commitment is critical; the on-going demonstration of leadership’s involvement is what drives and supports the system.

3. Communication Plan

A comprehensive communication plan, authored by leadership, is further evidence of its commitment to a problem solving culture. It should operate across the organization, informing everyone about: the status and results of problem solving projects, how these projects align with current strategy, the expectations for individual behavior, and leadership’s continued commitment. But more than just cascading missives from on high, it should foster communication up and down the organization, from meetings to reports to visual boards and newsletters, on daily, weekly and monthly schedules. Everyone must freely and frequently communicate problems up through the organization, and receive results and status back down. This is the way to change behaviors.

4. Make it Routine

Changing behavior to establish a problem solving culture requires the discipline to make new behaviors routine; you do it enough and it becomes a habit. This starts at the top with leadership, and this was exemplified by the “father of lean” Taichi Ohno who, as the story goes, regularly asked team members if they had any problems today. When a team member would say no, Ohno’s response would be “No problem is a big problem!” Eventually, they all understood – be on the constant lookout for problems, or else they would suffer Ohno’s displeasure!

But finding problems isn’t enough, they have to be exposed, and that brings us to a foundational feature of the problem solving culture – problems are exposed without fear of blame or recrimination. Leadership must set the example, and that lesson must cascade down through the ranks. Problems are nothing more than opportunities to improve, and when one is exposed the response is not “What did you do wrong?” but “How did we fail to see this coming and what can we do to prevent it in the future?” My own strategy is to prompt implementation teams to read aloud as a group a series of questions that I call “Did We?” It recites the failure modes of lean, and the goal is to honestly answer each question with “we did!” One question is “Did we allow too much complacency?” I teach them that one way to stamp out complacency is to conduct this problem dialogue with everyone they interact with at the “go and see” problem site (Gemba). Once the practice of solving problems with a sense of urgency becomes habit throughout your organization, the results can be miraculous.

5. Recognition

Many people are motivated not only by encouragement and direction, but also recognition, and it is leadership’s duty to set the example and recognize good work. A planned and standardized recognition system is the start to creating a culture of recognition. Every interaction (through governance, communication or routine activity) is an opportunity for intervention; whether to encourage good behaviors by recognizing them and their effects, or discourage bad behaviors through earnest and non-judgmental discussions.

Supporting behaviors aligned with the organization’s vision and strategy should, by example, cascade down. Of course that progress may be uneven. Sometimes you must be deliberate in where you apply the demonstrated behaviors. It may be a part of someone’s development plan; recognize your direct reports and peers for their good behavior and work!

These attributes of leadership, if followed and combined with a robust training program (see Part 1 of this series), can lead to the development of a problem solving culture. It is an opportunity available for the taking by any organization will to put in the effort. There is an old adage, “Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.” This one requires commitment and hard work, but the rewards are significant.

2019, Total Systems Development

2019, Total Systems Development 2019, Total Systems Development, Inc.

2019, Total Systems Development, Inc. 2019, Total Systems Development, Inc.

2019, Total Systems Development, Inc.